DELIBERATE SELF-HARM

Vulnerable groups at risk of suicide:

-Recent acute psychiatric illness, particularly during the first week after discharge.

-Schizophrenia, especially in patients who are poorly compliant or lost to follow up.

-History of drug or alcohol abuse.

-Any patient who says that they are feeling suicidal, especially if accompanied by feelings of hopelessness.

-Patients living in social isolation with no family support.

-Several previous episodes of deliberate self-harm.

-A single episode of deliberate self-harm carries 1 in 20 rate of suicide within 10 years.

Type of patients admitted with deliberate self-harm:

-The embarrassed and impulsive: the spur of the moment, often triggered by a row and alcohol, not necessarily a trivial amount (often paracetamol) and low risk of recurrence or future suicide.

-The serious attempt: a planned event, carried out alone and in secret, no attempt to get help, suicide note, admits to the intended outcome, even "trivial" overdoses may represent a determined attempt at suicide.

-The recurrent attender: severe personality disorder, history of violence, criminal convictions, drug and alcohol abuse, high risk of eventual success.

-The high-risk self-harm: older, male, isolated, unemployed/retired, alcohol dependence, poor general health, violent method used, repeated attempts and suicide note.

Why do patients deliberately harm themselves?: to gain temporary respite, as a cry for help, as a signal of distress, communicating anger/eliciting guilt/influencing others and to end their lives.

Critical nursing tasks in deliberate self-harm:

-Care of the unconscious patient: ABCDE (check observations, GCS, ECG, gain venous access, etc).

-Take appropiate blood (glucose, alcohol, paracetamol, aspirin, LFT, INR) and urine tests (opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy, hallucinogens).

-Decontamination of the gut: gastric lavage or activated charcoal (single dose or multiple doses).

-Ensure that all relevant information is available: mental state, past psychiatric history, previous self-harm, alcohol use, assessment of suicidal intent.

-Provide a suitable and safe environment in which to recover consciousness.

SPECIFIC OVERDOSES

- Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, unless taken as part of a more toxic cocktail, depress the consciousness level, but not sufficiently to put respiration at risk unless the patient also aspirates. Management is based on maintaining respiration and keeping a secure airway. The specific antagonist IV flumazenil reverses benzodiazepine coma immediately, but the drug has potential problems: the effects of a single dose soon wear off which may trigger acute agitation and if tricyclic antidepressants may also have been taken, flumazenil is contraindicated.

- Paracetamol

Paracetamol remains the most common cause of acute liver failure in the UK.

For most patients 12g of paracetamol or more than 150mg per kg body weight can produce severe liver damage.

Clinical picture of severe paracetamol toxicity:

-0-24 h: minimal immediate symptoms, mild nausea and vomiting within a few hours, liver function tests normal in the first 12 h, abnormal by 18 h.

-24-48 h: right upper abdominal pain with continued vomiting, liver tenderness, progressively deranged liver function tests, prolonged prothrombin time, loin pain, haematuria, proteinuria and deteriorating kidney function.

-Days 3 and 4: maximum liver damage on fourth day, jaundice and increasing confusion with grade 3/4 hepatic encephalopathy.

Immediate management:

-Establish the exact timing of the overdose (time tablets swallowed, time help arrived, could the overdose have been staggered over several hours?).

-what else was taken?

-is this a susceptible patient (eating disorder, HIV, cystic fibrosis or malnourished, chronic alcoholic, epileptic/anti-TB drugs, underweight).

-consider activated charcoal: overdose taken within an hour and methionine is not going to be used (charcoal inactivates methionine).

-take blood for measurement of. paracetamol levels.

-start N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex) treatment if indicated (patient needs to be weighed for the correct dose). Repeat LFT´s and prothrombin time at the end of the infusion (20 h).

There is a poor prognosis 24 h after the overdose, patients should be discharged only after psychosocial assessment, after completion of N-acetylcysteine and if there are no symptoms.

Clear instructions should be given to the patient who discharges themself: to return if there is abdominal pain, persistent vomiting or confusion.

- Antidepressants

There are two types of antidepressants used in deliberate self-harm:

-the older tricyclic antisepressants: these are dangerous and cause coma, convulsions and cardiac arrhythmias. Dothiepin is the most dangerous.

-the new generation of antidepressants (SSRIs). drugs like fluoxitine can cause "serotonin syndrome" - acute confusion, fever, muscular rigidity and twitching.

Management:

-The main dangers are: respiratory depression, cardiac arrythmias and convulsions.

-Patient remains at risk for at least 12 h after admission and are prone to arrythmias if they mobilise prematurely.

-Treatment: gastric lavage or single-dose activated charcoal.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide is odourless, colourless and extremely dangerous. Patients suffer hypoxic damage to the heart and central nervous system.

This gas has two important sources: incomplete combustion of carboniferous domestic fuel associated with faulty installations or accidental fires and car exhaust fumes.

Clinical picture:

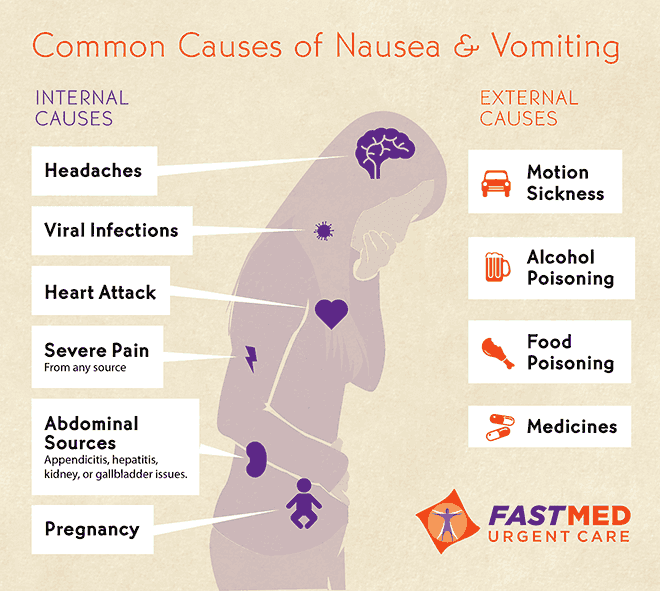

-Acute exposure: headache, nausea and dizziness progressing to collapse and loss of consciousness. In severe poisonng with coma, there may be skin blistering and pressure-induced muscle damage. The limbs are spastic and there may be acute heart damage, pulmonary oedema or increased intracraneal pressure.

-Subacute exposure: slower onset of nausea, vomiting, headaches and drowsiness. The clinical picture can mimic flu or gastroenteritis - a source of confusion. As with gastroenteritis, a whole household can be affected if exposed to the same source.

Assessment and management:

-ABCDE

-Give immediate high-concentration oxygen

-Consider hyperbaric oxygen, especially in cases of pregnancy, COHb > 20% or signs of neurological dysfunction

-If it is accidental domestic exposure, the local environmental health department should be involved to assess the safety of the house.

Source:

-A nurse´s survival guide to acute medical emergencies, R. Harrison and L. Daly, Elsevier 2011