PRINCIPLES OF EMERGENCY TREATMENT

1. Correct the immediate and life-threatening problems:

-Hypoxia (Oxygen, ventilation).

-Acidosis (Correct high arterial carbon dioxide).

-Hypotension (fluids +- inotropic support)

2. Treat the cause:

-Pulmonary oedema (diuretics, vasodilators).

-Bronchoconstriction (bronchodilators, steroids).

-Pulmonary embolism (anticoagulants).

-Pneumonia (antibiotics).

-Tension pneumothorax (intercostal drain).

3. Prevent further attacks:

-Asthma (education).

-Pulmonary oedema (Review previous cardiac therapy).

-Pulmonary embolism (warfarin).

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

Respiratory failure describes a state in which the lungs can no longer oxygenate the blood, and is diagnosed by measuring the arterial blood gases.

Several conditions have hypoxia without carbon dioxide retention, this pattern is termed Type 1 respiratory failure.

Some examples of Type 1 respiratory failure are: the early part of an attack of asthma, the thin breathless emphysematous patient, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema (LVF) or pulmonary embolism.

With more advanced disease in which the compensatory mechanism of trying to blow off carbon dioxide has "worn out", carbon dioxide retention (hypercapnia) occurs in addition to hypoxia. This is Type II respiratory failure.

Examples of Type II respiratory failure: severe life-threatening asthma, obese oedematous patient with severe COPD, respiratory centre depression in a severe drug overdose or obesity/hypoventilation syndrome.

Principles of treatment

For the treatment of respiratory failure to be effective, it must reverse the process by correcting the cause, which, depending on the disease, may include a combination of: airway narrowing, respiratory muscle weakness, alveolar damage, respiratory infection and/or impaired respiratory effort.

ACUTE SEVERE ASTHMA

Early in an attack of asthma, a combination of necessity and fear drives breathing sufficiently hard to blow off carbon dioxide. At this point, the levels of carbon dioxide in the blood are normal or low. In contrast, oxygen uptake is impaired and there is hypoxia, even at this early stage.

Later, as breathing tires, carbon dioxide builds up, oxygen levels continue to decrease and the patient´s condition becomes critical. The increase in carbon dioxide, which can be rapid and dramatic, now causes a sudden and dangerous decrease in blood pH. If this is unchecked, a respiratory arrest will follow.

Identify patients who are at risk:

-those who are tiring (history, observation and blood gases).

-those with severe airway narrowing (peak expiratory flow rate).

-those with hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation) and a build up of carbon dioxide (blood gases).

Signs of severe asthma:

-pulse rate of more than 110 beats/min

-a respiratory rate of more than 25 breaths/min

-the patient is too breathless to complete a sentence in one breath

-a PFR between a third and a half of their best or their predicted

Critical nursing tasks during the acute attack

-Give reassurance and support, provide explanations.

-Minimise the work of breathing.

-Monitor patient´s progress - key observations and tests: pulse, respiratory rate, PFR, oxygen saturations, blood pressure, temperature, urine dipstick (for steroid induced diabetes) and sputum colour (wallpaper glue sputum is common in asthma).

-Plan to prevent this happening again.

Click here for definition.

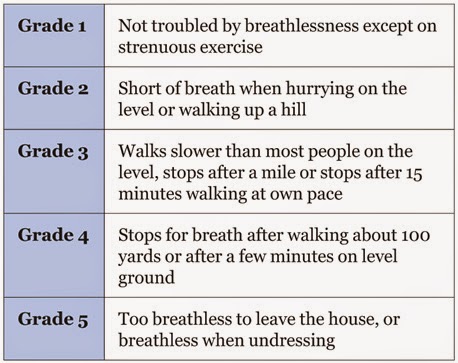

MRC breathlessness scale

Critical nursing observations: respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, peak flow rate, pulse rate, sputum colour and temperature.

Key questions: is the patient confused? (CO2 retention), is there effective cough?, is there ankle oedema?.

Management:

-Controlled oxygen therapy.

-Bronchodilators.

-Antibiotics.

-Oral steroids.

-Non invasive ventilation.

*Normal values in blood gases:

-pH: 7.36-7.44

-pO2: 12-14 kPa

-pCO2: 4.5-6.1 kPa

-HCO3: 23-28 mmol/L

PNEUMONIA

Pneumonia is a type of repiratory infection that leads to consolidation of part of the lung. Consolidation impairs gas exchange and is visible in the chest X-ray.

Signs and symptoms-breathlessness

-cough and sputum

-cyanosis

-chest pain (usually pleurisy)

-marked tachypnoea

-fever

-systemic illness.

The severity score in pneumonia: CURB-65

Critical nursing observations: respiratory rate, blood pressure, conscioussness, oxygen saturation, pulse, temperature, sputum colour, presence of pleuritic pain, evidence of mouth sepsis or/and airways disease.

Nursing tasks: provide timely therapy, provide explanations, monitor patient´s progress, assess the need for analgesia and watch for complications.

The effect of pneumonia on the patient:

-the extent of shadowing on the chest film

-ECG, look for atrial fibrillation, a common complication

-the degree of hypoxia (pO2 less than 8 kPa)

-the degree of acidosis (pH less than 7.3)

-WCC either less than 4 or more than 20 x 10(9)/L

-blood urea more than 7 mmol/L

-low serum albumin (less than 35g/L).

Management:

-fluid balance

-oxygenation

-appropiate antibiotics

-early mobilisation and DVT prophylaxis.

Complications:

-Pleural effusion and pleural empyema.

-Aspiration pneumonia.

SPONTANEOUS PNEUMOTHORAX

A spontaneous pneumothorax occurs when a defect on the surface of the lung "pops", letting air out under positive pressure into the pleural space. This pressurised air prevents expansion of the lung and can push the mediastinal structures to the opposite side of the chest. The symptoms are pain, breathlessness and, in severe cases, cardiorespiratory collapse.

Pneumothorax can be confused with three major conditions: pulmonary embolus, myocardial infarction and pleurisy.

A primary pneumothorax occurs in otherwise normal lungs, a secondary pneumothorax is caused by underlying lung disease or trauma.

Treatment involves removing the air from the pleural cavity by simple aspiration or, in more difficult cases, by placement of an intercostal drain.

Simple aspiration should be tried first, if aspiration does not lead to re-expansion of the lung, or if there is expansion followed by further collapse within 72hrs, then an intercostal drain will be needed.

Most of secondary pneumothoraces require tube drainage.

Nursing the patient with a chest drain:

-Gain consent unless it is an absolute emergency,

-Prepare your patient for the sterile procedure (reassurance)

-Positioning the patient: for example sitting in bed at 45 degrees with the appropiate arm behind his hea exposing the "triangle of safety",

-Alleviate the pain of the intercostal drain: if not contraindicated, a small dose of midazolam before skin incision can help the patient to be more relaxed and cooperative.

-Problems with intercostal drains falling out or falling apart, common problems: sutures that are too small, the weight of the connecting tubing pulling the drain out of the chest, untaped connections coming apart and failure to recognise or act on a displaced or disconnected tube.

Simple rules:

-Oxygen saturations should be monitored throughout the procedure.

-Use a transparent dressing so you can assess the state and site of the tube on at least twice a day basis.

-Bubbling tubes need to stay in and should never be clamped.

-Swinging tubes can probably be removed if the lung has expanded.

-Non-swinging tubes are often blocked.

Source:

-A nurse´s survival guide to acute medical emergencies, R. Harrison and L. Daly, Elsevier 2011.